The Lost Wax Process

The stages to the lost wax casting process are to make a mold, pour the wax, chase the wax, create a ceramic shell, de-wax and pour the metal, chip & sandblast the cast metal, weld all the pieces together, chase the metal, and apply the patina.

Click through the various production stages on your left to learn more about each step. If you would like additional information about our process, just give us a call!

History of Bronze and the lost wax process

The lost wax method of casting bronze is at least 6,000 years old. It was used in most of the ancient cultures, and without it the bronze masterpieces of Greece, Rome, Egypt, and the Near East could not have been created. It has always been employed for casting gold and silver as well. Today's lost wax method is used to produce nearly all bronze sculpture and is based on the ancient principles.

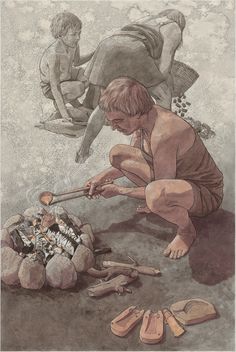

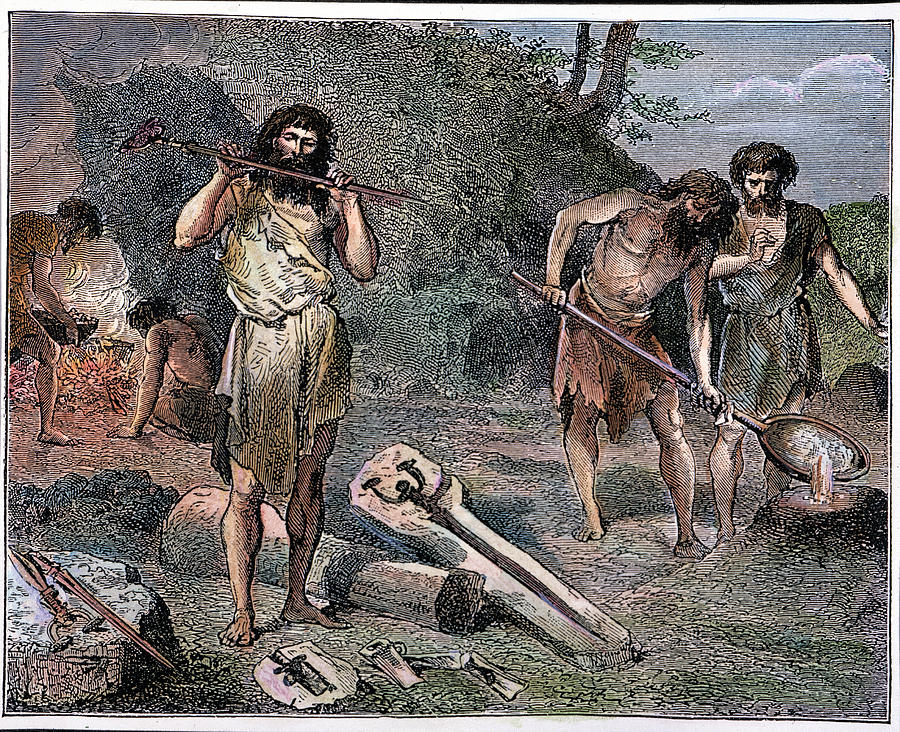

The first prehistoric artists who discovered the basic principle of lost wax casting, were only able to cast small crude, simple forms in solid metal. Later man learned to cast hollow bronzes of gigantic size and infinite refinement, but the same basic principle, wherever there was wax, there will be bronze, still held ture and holds true todya.

Most likely, with this rule in mind, those early primitive sculptors started with natural beeswax and created a small figure of a man, a horse, or an idol. When it was finished, they added wax extensions to the top and the bottom of the figure. Next, they completely enveloped the figure and extensions with a very thick coating of fine, liquid clay. But the ends of the wax extensions protruded slightly from this clay mold to form the simplest possible gate and vent system. This mold was heated in a fire until it was hard as a brink and the wax figure and the extensions inside were melted. They were burned out. They were gone forever- lost. Wax was replaced with air.

Bronze was melted, and poured into the cavity left by the lost wax. It was poured through the upper extension, called the gate, forcing the air out through the lower extension, called the vent. When the bronze cooled, the baked clay was chipped off, leaving the rough bronze casting. When the gate and vent extensions were removed, the small figure was smoothed with ancient versions of today's chisels, rasps and hammers. This was the first version of the lost wax method.

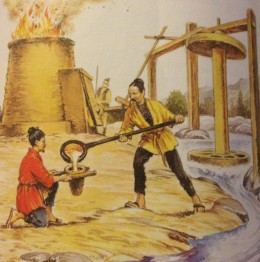

These early works were solid. The next major discovery occurred about 4,000 years ago during the Akkadian period in Mesopotamia. This was the method of casting bronzes with hollow interiors and only then did it become possiblt to cast larger works.

The French phrase for lost wax, cire perdue, is the most universally used term. To give an idea of the enduring prestige of the lost wax process, the Latin word, sincerus, meaning "without wax" originally applied to a lost wax bronze casting without a single imperfection. Sincerus is the root of our word, sincere, which to this day is defined as "real and true, without hypocrisy, embellishment, or exaggeration."

more History

Casting is one of the earliest of all metal-working methods. Prehistoric implements show a gradual progression from those crudely fashioned in stone to those cast in metal. One primitive casting method for making tools was to carve an impression of an ax-head into the flat surface of a stone slab. A funnel-like groove cut from the stone's edge directly to the hollow of the carved shape served as a sprue. The molten bronze or copper metals were poured into the mold through this groove. In some instances, a flat stone covering was placed over the carved area, which formed a contained mold. The Navajo Indians follow a similar procedure, carving designs in tufa (a fine-grained volcanic stone) to cast belt buckles, rings, pendants, and necklaces such as the famous design used in the Nezzah necklace with its hand-wrought squash-blossom links. Though the Navajos call this sand casting, it is not to be confused with sand castings that are made with foundry sand.

Eventually, casting progressed to the core method, in which the metal cast was just a skin thick enough to give strenth. Knights' American Mechanical Dictionary lists bronze as one of the first metals used for casting in the cire perdue or lost-wax casting method as early as 2230 B.C. In the Book of Isaiah (712 B.C.), mention is made of the calf cast in gold by Aaron, which was fashioned of molted metal and decorated with a graving tool. A bronze figure of Nero was cast by Zenodorus, a Greek craftsman, for the Colossus near the Temple of Venus in Rome. Museums now preserve some of the more famous productions of Lycippus and his Greek fellow-craftsmen, who were using the cire perdue method in the eighth century. Seville Cathedral in Spain has a candelabrum cast in 1562 by Bart Morel which remaids as an outstanding example of this method of casting. The numerous figures and statuettes, the foliage and the delicate scrollwork were all cast in bronze.